As the weather warms up, more outdoor runs means a greater exposure to ticks. Here’s how to prepare.

As the weather warms up, more of us head outdoors and wander off paved roads onto trails or into wooded areas to run. That, unfortunately, means a greater risk of exposure to ticks. While no one wants to deal with ticks, there are a few preventative steps we can take to help avoid tick bites and prevent tick-borne illnesses.

If you do happen to find a tick, there are a few important things you need to know. We talked to tick and infectious disease experts to find out everything from prerun tick prevention, to tick removal, to the signs, symptoms, and treatments of Lyme disease.

Tick Prevention: How To Avoid Tick Bites

If you live in a high-risk area, tick expert Thomas Mather, director of the University of Rhode Island’s Center for Vector-Borne Disease and Tick Encounter Resource Center advises spraying your shoes and running shorts with clothing-specific repellents containing permethrin. A coating of permethrin is effective for a month on your shoes and through 70 washings on your clothes. Mather prefers treating clothes with permethrin over DEET, which, depending on concentration, can lose effectiveness after 30 minutes.

If you’re running on trails or a park path, stick to the center and away from the edges where ticks tend to lurk. Ticks usually lie low in tall grasses (they’re not hanging out in trees waiting to hop onto you).

Regardless, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) wants runners everywhere to take precautions anytime ground temperatures are above 40 degrees, when ticks are most active.

“Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to predict whether or not there will be a lot of ticks from year to year,” said Rebecca Eisen, Ph.D., a research biologist with the CDC’s division of vector-borne diseases.

Runners, especially early morning runners, should be extra careful while working out in wooded areas, she said. On summer mornings, temperatures reach a sweet spot when it’s warm enough for ticks to be active, but not so warm that the hot and dry temperatures, in which the pests often die, are prevalent.

What To Do Before Going Outside

Before working out, Eisen recommends runners:

- Use repellents that contain 20 to 30 percent DEET on exposed skin.

- Use products that contain 0.5 percent permethrin, an insecticide that commonly treats lice, on your shoes, socks, and clothing.

- Remember to stay in the center of trail, where you are less likely to come into contact with the leafy habitat or grasses where ticks live.

What To Do After a Run

After working out, runners should shower as soon as possible. Ticks generally prefer warm, moist areas, so conduct a full-body tick check in a large mirror (checking under the arms, in and around ears, hair, inside the belly button, behind knees, between legs, and around the waist). You could also tumble dry workout clothes on high heat for 10 minutes to kill any ticks that may have smuggled their way into your shorts.

What To Do If You’re Bitten by a Tick

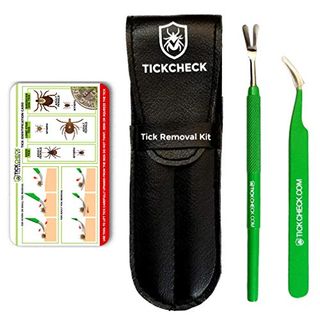

Remove It: Use pointy tweezers to grasp the tick as close as possible to your skin’s surface. Pull upward with steady pressure and avoid twisting or jerking it, which could cause some of the parts to break off in the skin. The video above shows you how, in detail.

Keep It: Mather recommends placing the tick in a resealable plastic bag and writing down the date of removal so you can show your doctor if you develop Lyme symptoms. You can also send your tick to a lab to get it tested; find out more here.

Sanitize: After removal, disinfect the bite area and wash your hands with soap and water.

Identify It: Different kinds of ticks carry different pathogens, so you’ll want to figure out the species that bit you. Mather’s TickEncounter Resource Center supplies photos to help you determine the type of tick and how long it might have been attached (ticks grow larger the longer they’re attached). Mather encourages you to take a photo of the tick and submit it to his resource center, which monitors tick activity.

When To Seek Medical Attention

If you remove an adult blacklegged tick that was attached to your skin for two days or more, you have a high risk of contracting Lyme disease, says Mather. And so he recommends contacting your doctor, who may give you a dose of the antibiotic doxycycline as a proactive measure. If a blacklegged tick was attached for less than a day, your risk of being infected is lower. But Mather still recommends saving the tick in case you begin feeling ill later. And of course, if you start to develop Lyme symptoms, see your doctor.

Quick tick removal lowers your risk of infection. Experts estimate that a tick must be attached for at least 24 to 48 hours to transmit the bacteria. But spotting one isn’t so easy. “The tick is very clever,” says Christine Green, M.D., an infectious disease specialist in San Francisco. “It wants to latch onto humans for a while, so it has evolved to put anesthetic chemicals on your skin so you don’t feel it so much.” Hard to feel and also hard to see, young ticks are the size of poppy seeds and love to burrow into hard-to-spot places like the groin, armpit, and scalp.

Unfortunately, the bacteria the tick can inject into your bloodstream is clever, too. “Lyme bacteria is highly evolved to evade our immune system’s detection,” says John Aucott, M.D., an infectious disease specialist and assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. When it enters the body, it folds itself up, origami-style, so the immune system doesn’t even know it’s there for about two weeks.

Interestingly, the bacteria isn’t wreaking havoc on your health; it is your body’s attempt to fight it off that makes you feel so crummy. “It’s a paradox, in that it’s not actually very dangerous itself,” Aucott says. “It’s an incredibly benign organism—it doesn’t want to kill the host, it wants to be undetected by the host.” You only know the bug is there when your immune system starts trying to kill it.

Lyme Disease Symptoms

Because Lyme symptoms tend to come on gradually, many people don’t initially notice the signs. And when they do recognize something’s amiss, Green says the early indicators—sluggishness, fatigue, muscle aches, joint pain—can easily be mistaken for the flu.

Or if you’re a runner, you may think you’re simply overtraining. “I’ve had athletic patients, runners and Nordic skiers, who thought their fatigue and aches were due to periods of hard training, but they were really suffering from Lyme,” says Bill Roberts, M.D., a sports-medicine physician at the University of Minnesota.

The longer a diagnosis is delayed and the later treatment is started (a three-week course of the antibiotic doxycycline is the standard therapy), the worse symptoms become. Patients start experiencing high fevers, migraines, dizziness, difficulty concentrating, stiff joints, and coordination issues, Green says.

Diagnosis becomes easier if you are lucky enough to get a red rash, the hallmark of the infection. But about 30 percent of people don’t get the rash and others don’t get one with the onset of symptoms. Adding to the confusion is that most people think the rash (the erythema migrans, as it is called) has to look like a distinctive bull’s-eye, but more often than not it’s simply round and spreads outward over time.

So suppose you do get the rash, and you do recall a tick bite. You might think it’s obvious that you have Lyme. But getting an official diagnosis is rarely that straightforward. In fact, there is no definitive diagnostic test for the infection—no method by which a doctor can detect the presence of the bacteria in a person’s body. Instead, the CDC-recommended blood test is indirect—meaning, it looks for the presence of Lyme-specific antibodies fighting the bacteria. And that makes it quite easy to get a false negative (early in the infection, before your body has produced antibodies) or a false positive (detecting antibodies because you have been exposed to the bacteria at some point in your life).

Which is why some doctors don’t rely entirely on the test for making a diagnosis. “The test can be helpful, but it shouldn’t be the be-all-end-all, whether it’s negative or positive,” says Alan Barbour, M.D., a professor of microbiology and molecular genetics at University of California at Irvine who is a fellow at the Infectious Diseases Society of America. “In an area where Lyme is common, doctors have gotten good at diagnosing it based on other symptoms, such as persistent flu-like symptoms occurring in the spring through fall in a person who spends time outdoors.”

How Long Symptoms Last

It’s a fact that some Lyme sufferers remain ill after the standard protocol of antibiotic treatment. According to the CDC, as many as 20 percent of patients continue to have chronic symptoms that can last for years. Doctors on both sides of the debate understand this. “If people don’t get treated right away, it can spread to other parts of the body and then you can have problems,” Dr. Barbour says. After the early symptoms of Lyme come on, the bacteria can then embark on a marathon slog through the bloodstream, infiltrating the joints, heart, and nervous system, which can produce an array of ongoing symptoms—from Bell’s palsy to cognitive issues, cardiac problems to chronic pain.

While researchers have recently given this phenomenon a medical term—Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS)—the exact cause of the “medically unexplained” symptoms remains a mystery. “If I knew that, I’d get the Nobel prize,” Aucott says. “That’s what our research is on, but no one knows. There’s no FDA-approved treatment for PTLDS, there’s no diagnostic test to know who’s going to get it and who isn’t. It’s pretty much a black box right now. This is a world-class dilemma. We think it is a real biological phenomenon; we just don’t know yet what it is.”

But the other side—championed by the International Lyme and Associated Disease Society (ILADS)—believes that the bacteria have not been killed off by a three-week course of antibiotics and continue to wreak health havoc. “I would say it’s more likely than not a persistent infection, but that has yet to be proven in people, and there are no current tests to tell us if the infection is gone or still there,” says Sam Donta, M.D., an infectious disease specialist and retired professor at Boston University Medical School. In his experience, long-term doses of drugs, such as oral tetracycline and erythromycin (when combined with hydroxychloroquine), knock out the infection: three to four months if the patient has been sick less than a year; 18 to 24 months if the patient has been sick for five years or more. “The National Institutes of Health has not agreed to have further treatment trials, and so it hasn’t been technically proven in double-blind trials,” says Donta, who is considered a “Lyme-literate” doctor, a name given to physicians willing to prescribe ongoing treatment. “So it is left to clinicians like myself who in their clinical experience have sorted out what works and what doesn’t work.”

Bottom line: As the weather warms up, take precautions before you head out to run that will help you avoid getting bitten by a tick. When you can, avoid long grasses and stay on the middle of the path. If you do find a tick on you, be sure to safely remove it as quickly as you can. Keep the tick in a resealable plastic bag incase you begin to develop symptoms, and if you do, contact your doctor right away.

Recent Comments