What causes type 2 diabetes?

By Dr. Austin Smith

Genes and environment can play a role in causing type 2 diabetes mellitus.

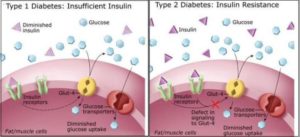

Let’s first take a step back. Type 2 diabetes develops when the body becomes less responsive to insulin, which is the hormone responsible for shuttling glucose (sugar) from the blood into various tissues throughout the body. Ordinarily, the body’s tissues are made up of cells that contain receptors that bind to insulin. These receptors allow insulin, and the glucose that’s bound to it, to enter the cell. If insulin struggles to bind to these receptors effectively, then glucose ends up remaining in the bloodstream, where cells are unable to use it for fuel. This is known as insulin resistance.

Eventually, the pancreas, which is the organ responsible for producing insulin, can burn out and the amount of insulin it can produce decreases. This is known as relative insulin deficiency.

Both insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency can become severe enough to cause type 2 diabetes.

And the causes for both insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency can be traced to one’s genes or environmental influences.

Rarely is it the case that just one gene is responsible for causing type 2 diabetes. More often, multiple genes play a role. These genes are involved in multiple processes throughout the body, including the development of the pancreas and the release of insulin.

Two of the most important environmental influences associated with type 2 diabetes are weight gain (although there are also genetic influences on weight) and decreased physical activity. Insulin resistance can be linked to obesity, and improved with weight loss. Exercise, too, can help improve insulin resistance.

Ultimately, if type 2 diabetes develops–be it from insulin resistance, relative insulin deficiency, or both–one’s ability to tolerate carbohydrates in the diet drops off significantly. For many, carbohydrates in the diet make up the majority of the body’s supply of glucose. And so if insulin isn’t being produced in normal amounts (relative insulin deficiency) or if insulin can’t bind to its receptors and shuttle glucose into the cells effectively (insulin resistance), then the glucose produced by the breakdown of carbohydrates will end up remaining in the bloodstream, where it can damage various organs.

Learn more about reversing diabetes through nutrition.

After about age 20, we may have all the insulin-producing beta cells we’re ever going to have in our pancreas, and so if we lose them, we may lose them for good. Autopsy studies show that by the time type 2 diabetes is diagnosed, we may have already killed off half of our beta cells.

You can do it right in a Petri dish. Expose human beta cells to fat; they suck it up and then start dying off. A chronic increase in blood fat levels is harmful, as shown by the important effects in pancreatic beta cell lipotoxicity. Fat breakdown products can interfere with the function of these cells, and ultimately lead to their death.

And not just any fat; saturated fat. The predominant fat in olives, nuts, and avocados gives you a tiny bump in death protein 5, but saturated fat really ramps up this contributor to beta cell death. Saturated fats are harmful to beta cells; harmful to the insulin-producing cells in our pancreas. Cholesterol too. The uptake of bad cholesterol, LDL, can cause beta cell death as a result of free radical formation.

So diets rich in saturated fats not only cause obesity and insulin resistance, but the increased levels of circulating free fats in the blood, called NEFAs, non-esterified fatty acids, cause beta cell death and may thus contribute to progressive beta cell loss in type 2 diabetes. And this isn’t just based on test tube studies. If you infuse fat into people’s bloodstream you can directly impair pancreatic beta cell function, and the same when we ingest it.

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by defects in both insulin secretion and insulin action, and saturated fat appears to impair both. Researchers showed saturated fat ingestion reduces insulin sensitivity within hours, but these were non-diabetics, so their pancreas should have been able to boost insulin secretion to match. But insulin secretion failed to compensate for insulin resistance in subjects who ingested the saturated fat. This implies the saturated fat impaired beta cell function as well, again within just hours after going into our mouth.

So increased consumption of saturated fats has a powerful short- and long-term effect on insulin action, contributing to the dysfunction and death of pancreatic beta cells in diabetes.

And saturated fat isn’t just toxic to the pancreas. The fats, found predominantly in meat and dairy—chicken and cheese are the two main sources in the American diet—are almost universally toxic, whereas the fats found in olives, nuts, and avocados are not. Saturated fat has been found to be particularly toxic to liver cells in the formation of fatty liver disease. You expose human liver cells to plant fat, and nothing happens. Expose liver cells to animal fat, and a third of them die. This may explain why higher intakes of saturated fat and cholesterol are associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

By cutting down on saturated fat consumption we may be able to help interrupt this process. Decreasing saturated fat intake may help bring down the need for all that excess insulin. So either being fat, or eating saturated fat can both cause that excess insulin in the blood. The effect of reducing dietary saturated fat intake on insulin levels is substantial, regardless of how much belly fat we have. And it’s not just that by eating fat we may be more likely to store it as fat. Saturated fats, independently of any role they have of making us fat, may contribute to the development of insulin resistance and all its clinical consequences. After controlling for weight, and alcohol, and smoking, and exercise, and family history, diabetes incidence was significantly associated with the proportion of saturated fat in our blood.

So what causes diabetes? The consumption of too many calories rich in saturated fats. Now just like everyone who smokes doesn’t develop lung cancer; everyone who eats a lot of saturated fat doesn’t develop diabetes—there’s a genetic component. But just like smoking can be said to cause lung cancer, high-calorie diets rich in saturated fats are currently considered the cause of type 2 diabetes.

A true love for sports

Recent Comments