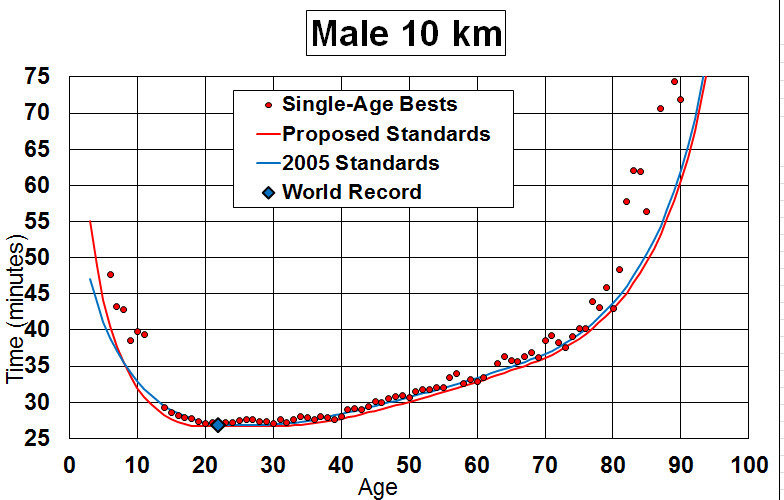

One indisputable effect of aging is declining aerobic horsepower. Classically, this is measured via VO2 max—or your maximum rate of oxygen usage per unit of body weight. For sedentary people, VO2 max typically declines by about 10 percent per decade after age 30. For athletes who keep in training, the rate of decline can often be held to about half that.

Most runners associate this with reduced cardiac capacity. With age, there is a steady fall in the number of receptors in your heart muscle listening to the nervous system’s signals telling it how fast to beat. As the heart becomes increasingly deaf to these messages, its maximum rate drops about one beat per minute each year.

There also appears to be a decline in the heart’s intrinsic ability to beat quickly. “It’s not so much that the heart can’t beat as quickly, though that’s probably true,” says Benjamin Levine, M.D., founder and director of the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital. “The heart can’t relax as quickly. Out of all the factors that are probably an inevitable part of aging and not modifiable by training patterns, this is it. Our data have shown that masters athletes have youthful, compliant— or ‘stretchy’—hearts that fill well at low pressures. However, no amount of training was able to prevent the slowing of relaxation.”

Many people simply presume that this decline in heart rate is the cause of age-related VO2 max decline. But the reality appears to be considerably more complex. What counts is the ability of the heart to pump blood, and that’s comprised of two factors: heart rate and stroke volume (the amount of blood pumped with each beat).

In one study, Levine and colleague Darren McGuire had a unique opportunity to study the effect of 30 years of aging on a small cohort of ordinary individuals. (Other long-term studies had involved elite athletes, a group that might not be representative of the rest of us.)

The study began in the 1960s, when five college students volunteered for three weeks’ total bed rest. Their catastrophic declines in aerobic conditioning are a major reason why nurses now prod surgical patients out of bed as quickly as possible. But before being put to bed, the young men were subjected to the type of testing normally reserved for elite athletes.

Thirty years later, McGuire and Levine retested the same men in their early 50s. The follow-up study revealed that the intervening decades hadn’t been as hard on their VO2 max values as the three weeks’ bed rest. Of greater interest, though, was the discovery that the men’s stroke volumes had increased. It was already known that this happens, as the heart enlarges to force blood through age-stiffened arteries. But nobody anticipated the magnitude of the effect. It turned out to be more than enough to compensate for the decline in maximum heart rate. A 50-year-old’s heart might not beat as rapidly as it once did, but it can pump at least as much blood per minute.

What this means is that changes in VO2 max aren’t entirely driven by changes in the heart. If the heart is delivering as much oxygen as before, but VO2 max is declining, it must be that the muscles are becoming less adept at using it.

What precisely is going on is a subject of considerable dispute. Partly, it’s simply that people lose muscle mass with age—smaller muscles use less oxygen.

But other factors are probably also involved. Perhaps aging muscles have fewer capillaries to supply them with blood. Maybe they’re less able to call for blood when they need it. Or perhaps their cells have fewer mitochondria (the powerhouses in which oxygen is used). Perhaps their arteries become increasingly clogged or inelastic.

A more complex theory comes from Tim Noakes, M.D., professor emeritus and former director of the Research Unit of Exercise Science and Sports Medicine at the University of Cape Town. He argues that for each stride, the aging brain may simply be using a lower fraction of the available muscle cells.

Physiologists have long known that for any given movement, our nerves recruit only a fraction of each muscle’s fibers, letting the others rest. In Lore of Running, Noakes suggests that as we age, our nervous systems may become more cautious about protecting our muscles from overload. (This is, however, an extremely controversial theory that has provoked outspoken dissent from other scientists.)

Whatever the cause, the solution is fairly straightforward: run. Others believe speedwork factors into the mix (reducing the number of longer runs). “Train fairly hard at your 2-mile or 5K pace at least once a week, where you’re running your heart rate up to 98 percent of maximum,” says Bob Williams, Portland-based running coach “I’m a real believer in that.”

McMillan agrees: “These are great things to include in your training program,” he says of 5K-paced workouts. “I wouldn’t say year-round, but frequently.”He also recommends racing frequently, perhaps once every three to six weeks, particularly 5Ks.

“That’s a great VO2 max workout in and of itself. The more I look at masters runners, the more I think you’ve got to keep racing. You almost go back to George Sheehan. He was the king of racing every weekend. It doesn’t have to be 100 percent, and you can’t do long. The more 5Ks and 8Ks you can do, the better. This is completely different from what you’d advise for a 23-year-old who wants to go to the Olympics.”

Flexibility

One of the people involved in McGuire and Levine’s study was Gregg Hill. At 20 years old, Hill was a college sophomore who ran a 4:45 mile. At the end of the follow-up study’s intensive training, his VO2 max had been restored—but not the 4:45 mile. Clearly, aerobic capacity isn’t the only factor affecting masters performance. “What determines speed on the track is different from VO2 max,” Levine says.

Also cutting into your speed is a simple loss of range of motion—a problem most runners have faced since youth, but which intensifies with age.

Part of the difficulty is the typical middle-aged lifestyle. McMillan notes that many masters-age runners spend a lot of their work lives sitting at their desks or in meetings. “We’ve risen to a level [in our jobs] that can be bad for us,” he says. “We’re doing a lot of things that don’t have us moving. That’s the worst thing we can do from a flexibility standpoint.”

Once your muscles start to get tight, you’re limiting your power base, according to Williams. “You’re not going to be able to move as smooth and efficiently.”

The solution is stretching. The idea is to get blood flowing through the connective tissues, best done by stretching them dynamically before the workout, and statically afterward.

Williams generally has runners do 15 to 20 minutes of dynamic drills while warming up. In particular, he says, dynamic exercises should focus on your calves, hamstrings, and hips.

But stretching isn’t the only thing that can help retain or restore flexibility. “Use a foam roller four to five days a week,” Williams says. “Or get a massage every week or two. The foam roller seems to be the primary tool I’ve found that keeps competitive runners healthy.”

5 Best Recovery Tools

Addaday Knot Bad

Tension release

$30 | REI

BUY NOW

GoFit Polar Roller

Ice without the mess

$30 | Amazon

BUY NOW

Hyperice Hypervolt

Relieves stiffness

$349 | Hyperice

BUY NOW

Normatec

Promotes circulation

$1495 | Amazon

BUY NOW

Roll Recovery R8

Deep-tissue massage

$129 | Roll Recovery

BUY NOW

Alternatively, if you want to retain flexibility but don’t want it to feel quite so regimented, Williams suggests trying some other sport that works your range of motion. Williams suggests tennis, but pretty much anything is better than nothing, even golf. “There are a lot of things you can do,” he says. “You don’t need a gym.”

McMillan agrees. Experiment with different types of flexibility training, he says. “As a masters runner, you’ve got to investigate and find the methods that work.”

[Run faster, stronger and longer with this 360-degree training program.]

Muscle Power

THOMAS BARWICKGETTY IMAGES

Another indisputable side effect of aging is a decline in muscle mass. According to the American College of Sports Medicine, muscle strength and mass begin decreasing at age 40, with the process speeding up after age 65 or 70. Of particular concern to runners, the loss generally occurs fastest in the lower body.

The rate of loss appears to be faster for fast-twitch fibers than for slow-twitch. That’s a greater problem for sprinters than for distance runners, but it should be of concern for everyone because it’s possible to lose all of your fast-twitch fibers. And when that happens, nobody knows how to get them back.

Scott Trappe, Ph.D., director of the Human Performance Laboratory at Ball State University, was the head of the team that made this discovery. The likely reason, he said at the time, is changing lifestyles. As people age, particularly into their 70s and 80s, they stop doing the high-intensity activities that call for fast-twitch fibers. The result is that these fibers atrophy until they’re gone—permanently.

“The body is going to react to demands,” adds Brown. “If you don’t demand it any more—if you think, ‘I’m too old to do this, and I’m not strong enough anyway,’ then you’ll start to lose muscle mass.”

The solution is vigorous weight training at whatever weight you can handle—and fancy gym machines aren’t necessary. Rubber tubing, free weights, stretchy bands, calisthenics— any of those can help. “As long as you’re doing something two or three days a week to push yourself to a point where you’re saying, ‘This is starting to get pretty hard,’” Williams says.

The best masters runners never stop, adds McMillan. “They seem to be always training and racing—that may help,” he says. “The initial research was showing that if you just keep with it, you can reduce that loss of muscle composition.”

Recovery

None of these approaches works if you push too hard, too often. “All the evidence I read doesn’t suggest that you can actually slow the aging process,” Noakes says. “In contrast, I think you can accelerate the aging process if you overdo the exercise.”

For younger athletes, he thinks overdoing it is running more than about two hours a day. But many masters runners find that it takes longer than it once did to recover from workouts and races. Lots of factors may be involved, but the simplest to understand is at the cellular level, where tissue repair and replacement simply don’t occur as rapidly as they once did.

What this means is that as you age, you may have to experiment with changing your workout pattern. According to McMillan, masters runners need to do every type of workout that younger runners do, but they may need to alter their schedules. And they may need to allow more time to adapt.

Stick with speedwork, a tempo run, and a long run each week but space them out. “ That’s going to be different for every runner,” he says. Masters runners also need to be careful to allow enough recovery time after races.

In the end, you can’t turn back time, but if you learn how to train smarter—not harder—as you age, there’s still a great chance you can nab a few more PRs.

A true love for sports

Recent Comments