Running isn’t a punishment—and all food is fuel, even that third helping of turkey and gravy.

Every year around the holidays, that tired joke about having to “run off” Thanksgiving dinner rears its ugly head. It’s the kind of aside that’s become so normalized, we don’t even think about how harmful the inherent food shaming can be.

Because—let’s get this out of the way right off the bat—there’s no reciprocal relationship between food and running. The idea that if you run more, you can eat more, or if you run less, you should eat less is totally false. That twisted thought pattern implies that you have to earn your food, or that running is punishment for eating. Nope. We run because we love to run, and we eat in a way that fuels our runs—it’s as simple as that.

“Eating is not a moral issue,” says Nancy Clark, R.D., author of Nancy Clark’s Sports Nutrition Guidebookand a weight coach for ultrarunners and marathoners. “Food is fuel, and there’s no such thing as good food or bad food. There’s a balanced diet and an unbalanced diet, and one meal does not throw off that balance.”

Same goes for the idea that holiday foods—such as fat-infused gravy and sugar-laden pumpkin pie—are “bad,” and indulging in them is bad behavior. “Food can not be good or bad, as every food contains some content of nutrients that our body needs to function appropriately,” says Katie Kage, R.D., an assistant professor in Nutrition and Dietetics at the University of Northern Colorado and an exercise physiologist.

That kind of thinking—any time of the year—creates a sense of guilt and shame around eating, something that’s meant to be enjoyed or necessary for function. And that’s an especially crappy way to feel around Thanksgiving, when you’re quite literally celebrating the abundance of a harvest, says Dorothy Beal, a RRCA- and USATF Level 1 run coach and body-positive activist. “Eating whatever your heart desires a couple of times a year isn’t going to hurt you,” she says. “I’d argue that the stress and anxiety linked to the shame and guilt an individual feels surrounding those indulgences do more harm to your body than just eating whatever you want, enjoying it, and moving forward.”

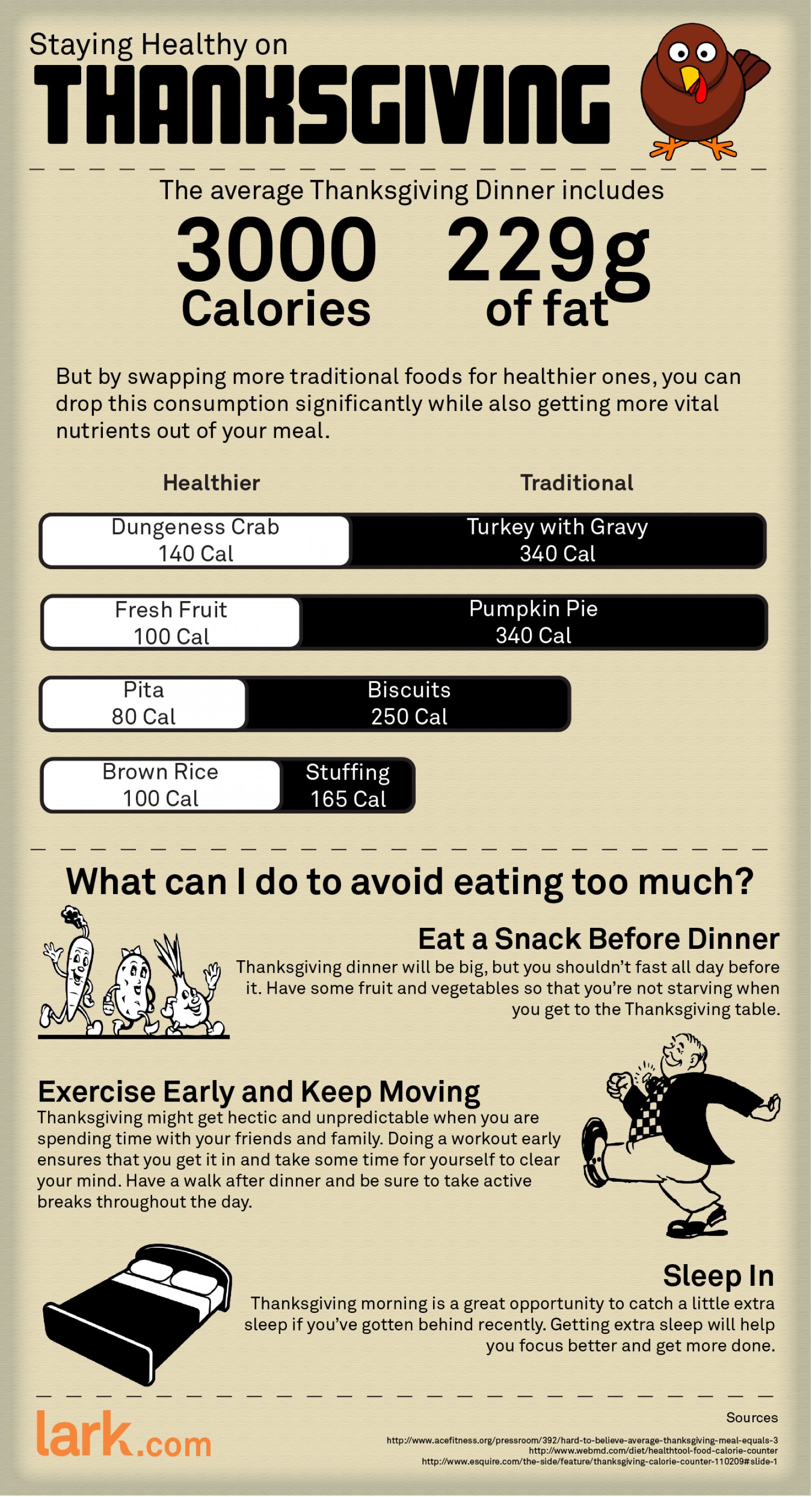

Yes, the average American may consume more than 4,500 calories and a whopping 229 grams of fat from snacking and eating a traditional holiday dinner with turkey and all the trimmings, according to research from the Calorie Control Council. (If you go by the general rule that one miles equals 100 calories, you’re looking at a 45-mile run to “run off” that meal.)

The reality is, you’re probably not consuming that many calories—and even if you did, “consuming more than the needed amount of calories in one day due to a holiday meal will not negatively impact your health in any way,” says Kage.

“Part of normal eating is overeating and feeling stuffed and uncomfortable,” adds Clark. That’s how your body learns where your limits are, and “part of normal eating is also trusting that your body will compensate for any overindulgences,” she says

Think about the last time you stuffed yourself on Thanksgiving turkey, gravy, and potatoes—you probably weren’t even hungry the next day. “If you listen to your body and its cues, you’ll realize it can course-correct on its own,” says Clark. Instead of “burning off” those excess calories, just don’t consume another 4,500 calories. Easy. And if you like, get in your normal run, walk with the family, or enter a Turkey Trot. But do so because it’ll make you feel great to exercise that day, not to “run off” your meal.

If you’re the kind of person who does weigh yourself, you may notice a few extra pounds on the scale after a holiday dinner. Don’t freak out—you didn’t gain three or four pounds of fat in one meal. “For each one ounce of glycogen you store in your muscles (from all the carbs in stuffing and potatoes), you store about three ounces of water,” says Clark. “Those extra pounds? That’s water weight, and you’ll likely lose it as soon as your diet goes back to normal.”

Instead of obsessing over what you ate and how to bring your body back to normal afterward, put food (and structured exercise) at the bottom of the priority list. “Holidays are meant to connect and grow relationships, so I always encourage people to incorporate activity with others during the holidays: Go for walks with grandparents, explore the outdoors with nieces and nephews, and engage in friendly competitions with siblings are all great ways to be active,” says Kage.

Whatever happens at the meal, don’t dwell on it. “You may feel terrible, that’s OK,” says Beal. “Move your body, eat nourishing foods, drink more water, get some sleep, and think about the happy memories you made to help get back a state where you feel ‘like yourself.’ Leave shame out of it.”

You can’t change what you ate or drank, but you can learn from it. “When you lie in bed that night, instead of beating yourself up, just evaluate what went right with the day and what went wrong,” says Clark. “How could you have eaten better or differently and what might you want to do next time? Were you trying to distract yourself from your feelings with food, or were you having fun and just enjoying yourself?” That may help you identify habits that can make you feel better the name time you’re contemplating a big meal—or you may be like, ‘I stuffed myself and I would do it again, because every bite was worth it.’ Either way, you win.

A true love for sports

Recent Comments